The Daily Reid: What, if anything, is Donald Trump doing to the 'Blacksonian?'

As the regime seeks to strip Black America of literally everything, all eyes are on DC's premier Black History Museum. But is it really under imminent threat from Donald Trump and JD Vance?

The “Blacksonian” isn’t just a building, or an institution. It’s OURS.

And buy “ours,” I mean Black America’s and by virtue of our foundational presence in this nation’s founding and development, ALL Americans’ as well. The plain fact is that there would be no United States of America, no U.S. empire, no “world’s richest country” and (former) leader of the free world without Black people. The American empire was founded on the land stolen from dozens of indigenous tribes, and built by the calloused hands, brutalized backs, and streaming sweat and blood of stolen African people whose free labor allowed European colonists to build unfathomable fortunes as plantation owners, who later rebelled against the English king because they wanted their gargantuan wealth to be tariff (AKA tax) free.

Someone needed to build a museum commemorating and documenting that history and put it on the National Mall. And finally, in 2003, congress agreed to do just that, creating what would become the largest museum African-American-focused museum in the world. Fittingly, the opening of National Museum of African American History and Culture, better known as NMAAHC as part of the Smithsonian Institution, was presided over by the first Black U.S. president, Barack Obama, in 2016. But getting a national Black history museum into the venerable Smithsonian family wasn’t easy.

Paging Mr. Smithson

The Smithsonian Institute dates back to 1846, when President James K. Polk, who no one ever thinks about anymore, signed its existence into law. Seventeen years before that, in 1829, a wealthy London aristocrat and French-born naturalized British citizen who also happened to be the illegitimate son of the 1st Duke of Northumberland, passed away, leaving a small fortune …

In 1829, James Smithson died in Italy, leaving behind a will with a peculiar footnote. In the event that his only nephew died without any heirs, Smithson decreed that the whole of his estate would go to “the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” Smithson’s curious bequest to a country that he had never visited aroused significant attention on both sides of the Atlantic.

Smithson had been a fellow of the venerable Royal Society of London from the age of 22, publishing numerous scientific papers on mineral composition, geology, and chemistry. In 1802, he overturned popular scientific opinion by proving that zinc carbonates were true carbonate minerals, and one type of zinc carbonate was later named smithsonite in his honor.

Six years after his death, his nephew, Henry James Hungerford, indeed died without children, and on July 1, 1836, the U.S. Congress authorized acceptance of Smithson’s gift. President Andrew Jackson sent diplomat Richard Rush to England to negotiate for transfer of the funds, and two years later Rush set sail for home with 11 boxes containing a total of 104,960 gold sovereigns, 8 shillings, and 7 pence, as well as Smithson’s mineral collection, library, scientific notes, and personal effects. After the gold was melted down, it amounted to a fortune worth well over $500,000. After considering a series of recommendations, including the creation of a national university, a public library, or an astronomical observatory, Congress agreed that the bequest would support the creation of a museum, a library, and a program of research, publication, and collection in the sciences, arts, and history. On August 10, 1846, the act establishing the Smithsonian Institution was signed into law by President James K. Polk.

That gift to America has spawned a veritable treasure chest of museums in the nation’s capitol:

Today, the Smithsonian is composed of several museums and galleries including the National Museum of African American History and Culture, nine research facilities throughout the United States and the world, and the national zoo.

Besides the original Smithsonian Institution Building, popularly known as the “Castle,” visitors to Washington, D.C., tour the National Museum of Natural History, which houses the natural science collections, the National Zoological Park, and the National Portrait Gallery. The National Museum of American History houses the original Star-Spangled Banner and other artifacts of U.S. history. The National Air and Space Museum has the distinction of being the most visited museum in the world, exhibiting such marvels of aviation and space history as the Wright brothers’ plane and Freedom 7, the space capsule that took the first American into space. James Smithson, the Smithsonian Institution’s great benefactor, is interred in a tomb in the Smithsonian Building.

NMAAHC, however, didn’t come about easily. The history is nearly as long as America is old…

100 Years In The Making, Black History And Culture Museum Gets Ready For Reveal

September 14, 2016

When peals ring out from a 130-year-old church bell at the Sept. 24 dedication ceremony for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, they will signal the end of a long journey.

The historic "Freedom Bell" usually hangs in Williamsburg, Va., in the tower of the First Baptist Church, which was founded by slaves. It started making its way to Washington, D.C., on Monday, according to The Associated Press, in order to herald this latest historical event.

"The connection between a congregation founded in 1776, the forging of First Baptist Church, the first black president opening the first national African-American museum, all of those dots are being connected," the Rev. Reginald Davis told WVEC.

But in truth, it took more than a few people, and a century's worth of starts and stops, to shift the museum from conversation to construction.

"A long time coming"

The idea of the museum was first proposed in 1915 by black veterans of the Civil War. A year later, Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer, R-Mo., introduced HR 18721, a bill that called for a commission to "secure plans and designs for a monument or memorial to the memory of the negro soldiers and sailors who fought in the wars of our country."

Three years later, Dyer — who also authored the 1918 Dyer Anti-Lynching bill — upped the ante and drafted a bill to erect an African-American monument in the capital. In Begin with the Past: Building the National Museum of African American History and Culture, author Mabel Wilson writes that Dyer's 1919 bill "sparked a round of discussions among the various committees overseeing federal land." There was even talk of building the memorial on the National Mall, but a decision on how to pay for it was put off.

In 1929, things looked hopeful again when Congress passed legislation establishing a commission charged with building an African-American memorial. But once again, no money was allocated for it — it was the Depression — and the project lost momentum.

The museum gained new champions during the civil rights era, but it wasn't until 1986 that Congress passed a joint resolution supporting private efforts to build it. The efforts inched forward in 1991 when a Smithsonian blue-ribbon commission pushed for creation of the museum, recommending that the iconic, red-brick Arts and Industries Building be its temporary home. But political squabbles over funding and a site location stymied that effort.

The arrival of the new millennium, however, seemed to bring with it new momentum to get the museum built. In 2003, Congress passed the National Museum of African American History and Culture Act, a bill making the museum part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Over the next few years, a board was selected and more than $240 million was raised from donors such as Oprah's Charitable Foundation, Samuel L. Jackson and his family, Michael Jordan and his family, the LeBron James Family Foundation, the Kobe and Vanessa Bryant Family Foundation, Earvin and Cookie Johnson and family, and Mellody Hobson and George Lucas. The federal government kicked in $270 million.

"They took advantage of having the first African-American president, and of President Obama's legacy," Emmett Carson, president and chief executive of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation and an authority on African-American giving, told The Washington Post in May.

The other pieces fell into place once the location was decided in 2006: an architecture design team selected in 2009, and finally, in February 2012, a groundbreaking.

"This day has been a long time coming," Obama said during the ceremony.

Here’s how The New York Times reported the museum’s launch:

Sept. 4, 2016

Eleven years ago, Lonnie G. Bunch III was a museum director with no museum.

No land. No building. Not even a collection.

He had been appointed to lead the nascent National Museum of African American History and Culture. The concept had survived a bruising, racially charged congressional battle that stretched back decades and finally ended in 2003 when President George W. Bush authorized a national museum dedicated to the African-American experience.

Now all Mr. Bunch and a team of colleagues had to do was find an unprecedented number of private donors willing to finance a public museum. They had to secure hundreds of millions of additional dollars from a Congress, Republican controlled, that had long fought the project.

And they had to counter efforts to locate the museum not at the center of Washington’s cultural landscape on the National Mall, but several blocks offstage.

“I knew it was going to be hard, but not how hard it was going to be,” Mr. Bunch, 63, said in an interview last month.

In less than three weeks, though, with President Obama presiding, the new museum, a project that once thirsted for money, land and political support, is scheduled to open on the Mall.

Visitors to the $540 million building, designed to resemble a three-tiered crown, will encounter the sweeping history of black America from the Middle Passage of slavery to the achievements and complexities of modern black life.

But also compelling is the story of how the museum itself came to be through a combination of negotiation, diplomacy, persistence and cunning political instincts.

The strategy included an approach that framed the museum as an institution for all Americans, one that depicted the black experience, as Mr. Bunch often puts it, as “the quintessential American story” of measured progress and remarkable achievement after an ugly period of painful oppression.

The tactics included the appointment of Republicans like Laura Bush and Colin L. Powell to the museum’s board to broaden bipartisan support beyond Democratic constituencies, and there were critical efforts to shape the thinking of essential political leaders.

Today, NMAAHC is the second most visited site among the sprawl of picturesque Smithsonian museums on the National Mall, the most visited Black history site in the U.S. and one of the most visited museums of any genre in the United States. It houses some 40,000 objects in its collection, with a combination of loaned items (about 1.2 percent of the total) and the vast majority of artifacts and displays that are part of the museum’s permanent collection. Of that total, about 3,500 items are on display at any given time in the massive, 350,000-square-foot, 10-story facility, of which five floors are underground.

A tour of the Blacksonian, as the community calls it (reportedly over the objections of Dr. Bunch, while museum employees call it ‘nah-MOCK”) starts with a long, emotionally jarring elevator ride to the bottom floor, where one experiences the dark descent into enslavement in visceral terms. After that, you rise from floor to floor, experiencing the deep pain and intense joy and cultural ascendancy of being African in America. It’s truly a one of a kind experience, which actually takes a couple of day trips to fully enjoy (there’s also a great restaurant to take your family too since they will get hungry with all of that walking.) Inside the museum, you’ll experience everything from the tiny chains affixed to the wrists and around the necks of tiny African enslaved children, to Rev. Al Sharpton’s 1980s sweat suits and o.g. hip hop beat boxes, to the original costumes from the 1970s Broadway production of The Wiz and a photo journey of Barack Obama’s road to the White House. It’s a massive, thoroughgoing journey through American Blackness.

It is for that reason that Black folks love … and I mean LOVE … the Blacksonian. And any threat to its existence is read by the community writ large (perhaps with the exception of Clarence Thomas, Byron “Black families were better off during Jim Crow” Donalds and a few others) as a personal attack.

So you can imagine the alarm bells that went off when Donald Trump issued his offensive, ugly March 27 executive order banning so-called “improper ideology” from the nation’s public museums, national parks and cultural institutions. It came in the midst of his regime’s frenzied attempts to delete Black history and heroes, from Medgar Evers to Jackie Robinson to the Tuskegee Airmen from the military’s official websites and Arlington National Cemetery’s online visitor’s guide, the clumsy deletion and quick reversal on removing Harriet Tubman’s connection to the underground railroad, and news that the General Accounting Office would potentially begin selling off the Black history treasures owned and managed by the National Parks Service. Word began to spread that the Blacksonian was next, since Trump’s order specifically called out the NMAAHC:

Section 1. Purpose and Policy. Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our Nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth. This revisionist movement seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light. Under this historical revision, our Nation’s unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness is reconstructed as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed. Rather than fostering unity and a deeper understanding of our shared past, the widespread effort to rewrite history deepens societal divides and fosters a sense of national shame, disregarding the progress America has made and the ideals that continue to inspire millions around the globe.

The prior administration advanced this corrosive ideology. At Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — where our Nation declared that all men are created equal — the prior administration sponsored training by an organization that advocates dismantling “Western foundations” and “interrogating institutional racism” and pressured National Historical Park rangers that their racial identity should dictate how they convey history to visiting Americans because America is purportedly racist.

Once widely respected as a symbol of American excellence and a global icon of cultural achievement, the Smithsonian Institution has, in recent years, come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology. This shift has promoted narratives that portray American and Western values as inherently harmful and oppressive. For example, the Smithsonian American Art Museum today features “The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture,” an exhibit representing that “[s]ocieties including the United States have used race to establish and maintain systems of power, privilege, and disenfranchisement.” The exhibit further claims that “sculpture has been a powerful tool in promoting scientific racism” and promotes the view that race is not a biological reality but a social construct, stating “Race is a human invention.”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has proclaimed that “hard work,” “individualism,” and “the nuclear family” are aspects of “White culture.” The forthcoming Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum plans on celebrating the exploits of male athletes participating in women’s sports. These are just a few examples.

It is the policy of my Administration to restore Federal sites dedicated to history, including parks and museums, to solemn and uplifting public monuments that remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage, consistent progress toward becoming a more perfect Union, and unmatched record of advancing liberty, prosperity, and human flourishing. Museums in our Nation’s capital should be places where individuals go to learn — not to be subjected to ideological indoctrination or divisive narratives that distort our shared history.

To advance this policy, we will restore the Smithsonian Institution to its rightful place as a symbol of inspiration and American greatness –- igniting the imagination of young minds, honoring the richness of American history and innovation, and instilling pride in the hearts of all Americans.

It’s giving Chris Rufo, the faux intellectual who popularized the politically advantageous right wing freakout over Critical Race Theory (here’s the time I debated him on The ReidOut) in that it reflects the wider right wing war on so-called “woke” ideology in every social and educational institution. Rufo has built a whole business model around injecting the Republican Party with inchoate terror over the widely popular, Pulitzer Prize winning 1619 Project, and the fear that Black people being centered in U.S. history as anything other than happy slaves singing in the fields and grateful to America and its kind, generous founders for their lifetime, hereditary employment will bring about the collapse of Western civilization. Rufo has essentially taken control of Florida governance through the puppeteering of pudding-fingered careerist Ron DeSantis, and now he’s leading the charge for Donald Trump to take personal control over American universities and other institutions, to rinse them lily white of all that improper insistence that Black live matter, what the right calls “gender ideology,” meaning the insistence on trans people existing, the “Palestinian kids shouldn’t be flattened by 2,000 pound bombs at school” protests, and any American openness to non-white immigration.

The zeal to erase the 1619 Project and any rethinking of American history as fed to us in elementary and high school by the Daughters of the Confederacy and their modern day fellow travelers runs deep in the Project 2025 playbook being used by the current regime as its governmental operations plan. It runs even deeper in the wider demographic panic by the American right, as we approach the end of America’s white majority in roughly 2045.

Related read: the conspiracy theory right’s plan to make more white people before the end is nigh

In other words, anyone worried about this regime attacking every Black institution, achievement, enterprise, Historically Black College and/or museum including NMAAHC, isn’t out of their mind.

So, is JD Vance dismantling the NMAAHC?

Unlike the National Parks Service, which falls squarely under the authority of the executive branch, The Smithsonian Institution is a public-private partnership governed by a 17-member board of regents, who don’t answer to the president. Here’s how that works, per the Smithsonian website:

Congress vested responsibility for the administration of the Smithsonian in a 17-member Board of Regents.

As specified in the Smithsonian's charter, the Chief Justice of the United States and the Vice President of the United States are ex officio members of the Board, meaning that they serve as a duty of their office. The Chief Justice also serves as the Chancellor of the Smithsonian. [Emphasis added]

There are six congressional Regents: three Senators are appointed by the President pro tempore of the United States Senate and three Representatives are appointed by the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. Their terms on the Board coincide with their elected terms in Congress, and they may be reappointed to the Board if reelected.

Nine Regents are from the general public, two of whom must reside in the District of Columbia and seven of whom must be inhabitants of the 50 states (but no two from the same state). Each is nominated by the Board of Regents and appointed for a statutory term of six years by a Joint Resolution of the Congress, which is then signed into law by the President. In accordance with the Bylaws adopted by the Board of Regents in 1979, citizen members may not serve more than two successive terms.

According to NMAAHC sources, most U.S. vice presidents — while de facto members of the board, don’t typically attend the quarterly board meetings, and Vance didn’t attend the recent one on April. But Trump’s executive order deputized Vance and another official: Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and Special Assistant to the President and Senior Associate Staff Secretary, Lindsey Halligan, Esq., to “work to effectuate the policies of this order through his role on the Smithsonian Board of Regents with respect to the Smithsonian Institution and its museums, education and research centers, and the National Zoo, including by seeking to remove improper ideology from such properties, and shall recommend to the President any additional actions necessary to fully effectuate such policies.”

Again, this was not Trump appointing Vance to the board of regents — he was already on it by default by virtue of becoming vice president — but it was a case of Trump asking him to do something undetermined, regarding the museums and other Smithsonian properties (though he couldn’t do anything on his own — it would require a majority board vote and potentially congressional action to fundamentally alter the museum.) But Trump’s edict to Vance was enough to raise alarms, given the anti-Black, anti-woman, anti well … anyone who isn’t a conservative Christian white male bent of the regime.

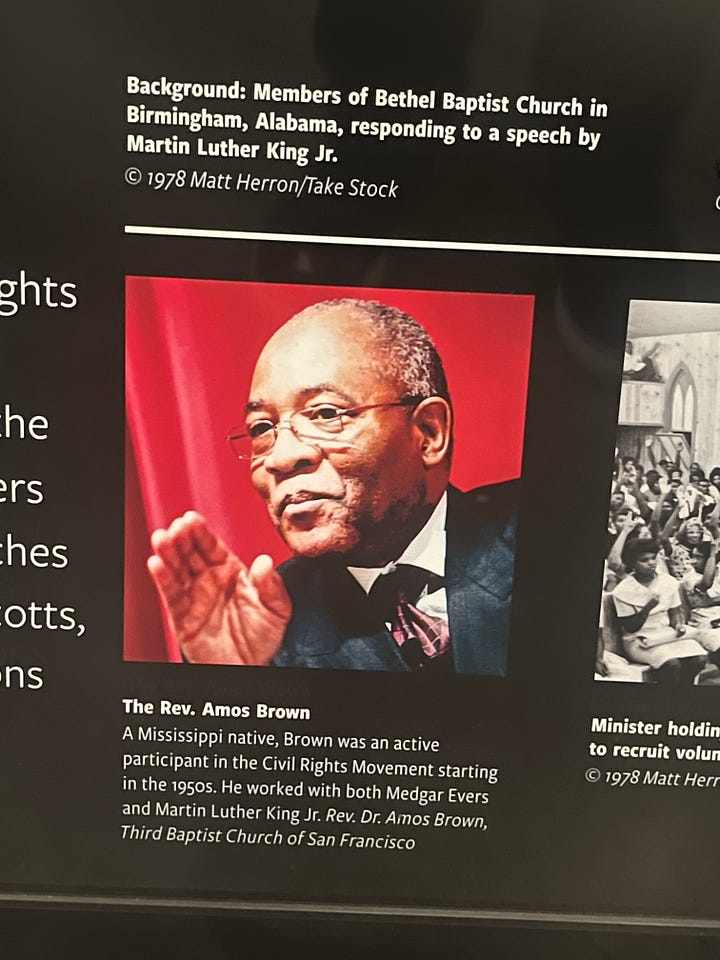

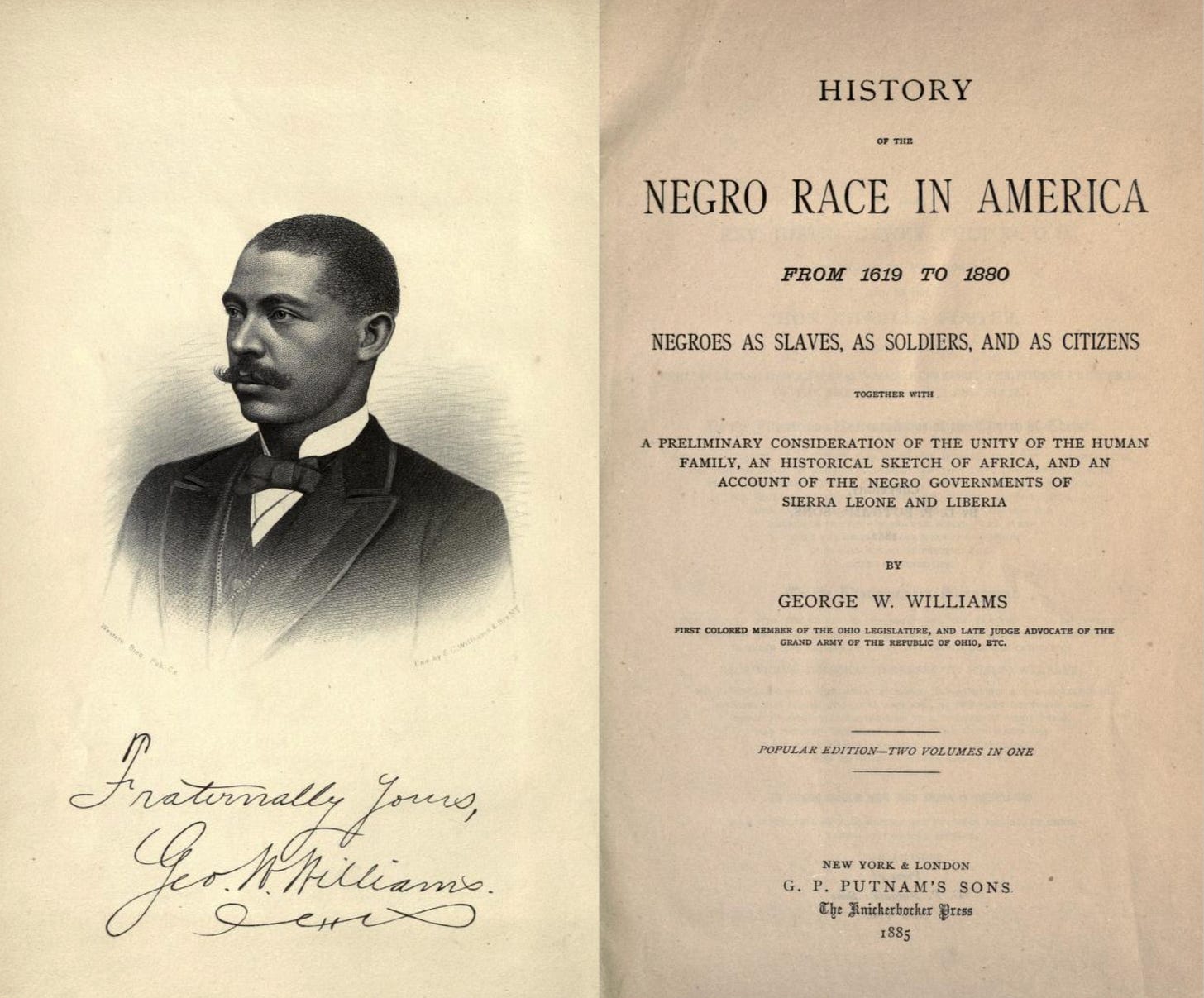

Last week, a story in Black Press USA, the consolidating entity of the trade union representing the nation’s historic Black newspapers, stated that items inside the Blacksonian were being removed from display or returned to their owners as a result of that directive. In the story, Black Press USA’s White House correspondent April Ryan, recounted the experience of Rev. Dr. Amos Brown, a former mentee of Medgar Evers and student of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Morehouse College, who said he received an email in April from a NMAAHC staffer informing him that two items he had loaned to the museum in 2014 to be part of the 2016 founding collection — a family Bible that had been in his family for generations and a copy of History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880; the seminal book by civil war veteran, military fighter in Mexico, Howard University collegian, ordained Baptist minister, lawyer, Ohio state legislator and author George Washington Williams, published in 1882 — would be returned to him in May.

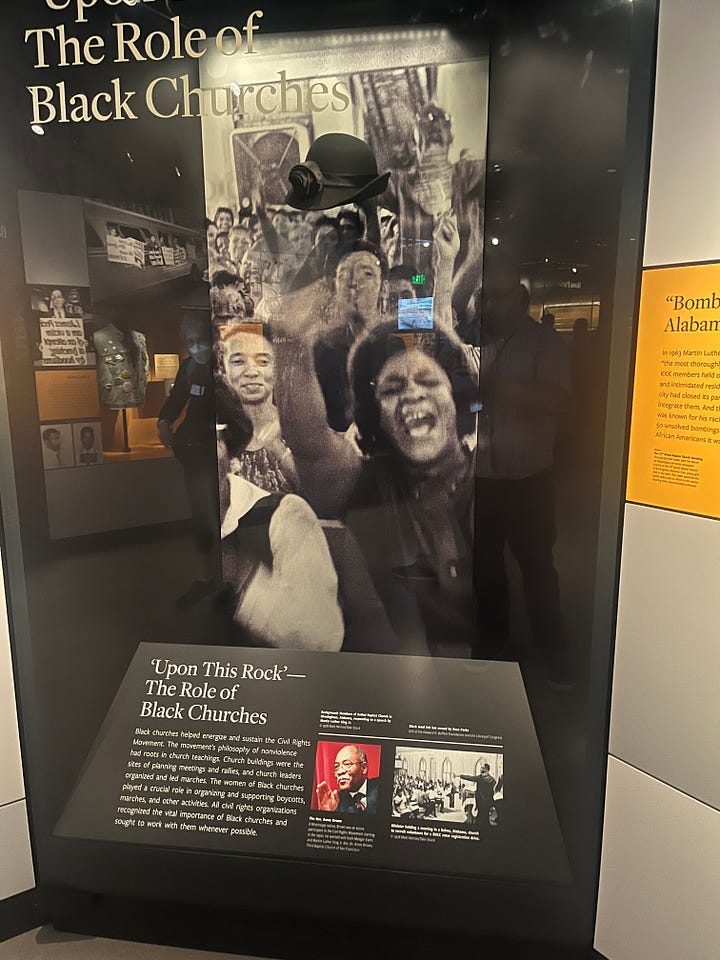

Rev. Brown is the subject of his own display at the museum, as part of an exhibit entitled: "Upon this Rock - the Role of Black Churches” in the civil rights movement.

I interviewed and wrote about Rev. Brown for my book, Medgar and Myrlie, recounting his experience, protesting for civil rights as a 15-year-old high school student in Jackson, Mississippi and being tutored in social action by Mr. Evers. Rev. Brown went on to become an NAACP leader in his own right, and notably, pastor at San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church to one Kamala Devi Harris, former California attorney general - turned United States Senator - turned Vice President of the United States and 2024 candidate for president. And I was among the people he called after he received that email.

Based on two conversations we had by phone, the notice of return alarmed and offended Rev. Brown, particularly given the context of rampant mistreatment of Black history and historical figures by the Trump regime, including his mentor, Mr. Evers. About 40 percent of NMAAHC’s programming is federally funded, while the remainder is funded through private donations and ticket sales, which means the museum is at least partially vulnerable to potential federal recriminations.

Brown noted when I spoke with him that Dr. Bunch had responded publicly to Trump E.O., by reaffirming NMAAHC’s independence, which to Brown, made him a potential target for Trump-style retribution. Indeed, many in the Black community, including civil rights leaders and activists, had been concerned for Secretary Bunch’s continued longevity at the Smithsonian with Trump and Republicans in charge, and holding a majority of seats on the board.

Raising further alarm was the reporting in the same Black Press USA story that a display of two stools used in the 1960 Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina were also being removed from the museum, as part of what the report implied was a larger dismantling of the museum’s authentic Black American history.

The story immediately went viral, producing numerous high profile reposts and versions of the story in several other news outlets (I also reposted the original story on my Bluesky and Threads accounts, though I subsequently deleted them.) There was immediate pushback, including from a Washington Post arts writer who debunked some of the most alarming claims in the original piece, and clarified that the Greensboro Woolworth’s lunch counter exhibit is largely housed at a different D.C. museum (though two of stools from the original lunch counter are displayed in rotation at NMAAHC.)

After seeing that reporting, and after Black Press USA posted a follow up story saying the plan to remove the Woolworth’s display was retracted due to the original story; an assertion that was disputed by multiple sources close to the museum who contacted me, concerned that the story was creating a false panic, and distracting from the very real and imminent attacks on other entities such as the National Parks Service cache of Black history monuments, I made some calls.

Sources I spoke to with direct knowledge of museum operations assured me over the weekend and on Monday that there was never any intention to dismantle the museum’s Black history content, that Trump’s executive order dealt with “ideology,” not objects and that NMAAHC staff had not at that point been contacted by either Vance or Ms. Halligan, and that the stools in question were merely being rotated — so that one always remained on display while the other was kept in storage, to maintain their physical condition. It was also pointed out to me that 68 percent of NMAAHC’s federal and trust positions are filled by Black women “doing the work and leading the charge at the museum.” This was hardly a group itching to bend the knee to Trump’s ideological plans for NMAAHC, although there was also concern that raising the alarm without factual foundation was putting a needless spotlight on museum workers who were simply doing their jobs.

As for the Bible and book loaned by Rev. Brown, a museum source told me the Bible and book, which were originally loaned by Rev. Brown to NMAAHC in Nov. 2014, in preparation for the opening exhibitions in 2016, had been the subject of two loan renewals: one for two years, beginning May 2020 and ending in May of 2023 (excluding the several months the museum was closed during the COVID pandemic, when no exhibits were open) and a second, also for two years, from May 2023 until May 31, 2025. And that because they had essentially been on continual display for eight and a half years, there was concern about their physical condition. (Rev. Brown disputes that assertion, saying a museum should know how to care for old objects.) I was told by sources close to museum operations, that since the notification has been made that the second renewal period has expired, Rev. Brown will likely receive his items before the May 31 deadline.

“Per Smithsonian (and museum industry policy) we do not keep artifacts after their loan agreements expire,” a museum source told me on background. “Loan agreements are signed by both parties.” I was told by a separate source close to the process that Rev. Brown has since been offered the option of extending the loan of his materials, or gifting them to the museum to add to their permanent collection. I confirmed with Rev. Brown that such a process was offered, but he insisted that it was only offered after he vocally objected to the attempted return of his items against his wishes, and after he “jammed them up” by going public. I reached out to Museum officials and Rev. Brown requesting copies of the signed loan documents, but have not received a response as yet. I’ll keep trying.

As of our most recent conversation late Monday, Rev. Brown is standing by his initial assertion that the return of his items is part of a larger attack by the Trump regime on NMAAHC and on Black history, and was disrespectful to him and to Black America. He has since done media appearances saying as much. April Ryan is fervently standing by her original reporting as well.

Here is the full statement released by NMAAHC on April 28:

Recent reports about the Smithsonian removing the historic Greensboro, North Carolina, lunch counter and a stool from the National Museum of American History and National Museum of African American History and Culture, respectively, are inaccurate.

Both the Greensboro lunch counter and stools where college students sat in protest during the Civil Rights Movement are and continue to be on display. A stool from the sit-ins remains on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture as the centerpiece of an interactive exhibition. The larger section of the Greensboro counter also remains on display at the National Museum of American History. Suggestions that the Smithsonian had planned or intended to remove these items are false.

Further, the Smithsonian routinely returns loaned artifacts per applicable loan agreements and rotates objects on display in accordance with the Smithsonian’s high standards of care and preservation and as part of our regular museum turnover. Recent claims that objects have been removed for reasons other than adherence to standard loan agreements or museum practices are false.

As the steward of our nation’s treasures and history, the Smithsonian preserves and protects all objects and artifacts in its collection to ensure their long-term conservation and to safeguard them for future generations.

And here is how NMAAHC describes its mission on its website:

Our mission is to capture and share the unvarnished truth of African American history and culture. We connect stories, scholarship, art, and artifacts from the past and present to illuminate the contributions, struggles, and triumphs that have shaped our nation. We forge new and compelling avenues for audiences to experience the arc of living history.

You can trust and believe that Black America and our allies will fight to keep it that way. And the deep mistrust most African-Americans feel toward Trump, Vance and the rest of the Project 2025 clan will keep heads on a swivel when it comes to Our Museum, and all of the treasured museums and historic National Parks sites in and outside the Smithsonian (Vance's board membership also gives him eyes on the Women’s History Museum and nearly 20 other Smithsonian properties including the National Zoo.

I’ll keep an eye on this story and will report back on any developments.

[This post has been updated.]

So glad you covered this. I just heard it and was pissed off but skeptical. If they touch the Blacksonian I’d be there protesting.

Thank you, Joy, for keeping this matter in the spotlight. The threats against the National Museum of African American History and Culture Museum are not to be taken lightly. After hearing that the exhibit was purportedly removed, I visited the NMAAHC on Saturday, April 26th, along with visiting the exhibit in the National Museum of American History. They were both intact. People at both exhibits were engaged with them. I took pictures and I wrote about it in my Substack: https://open.substack.com/pub/mbmatthews/p/on-lunch-counters-history-and-truth?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=hcg5.

The person who should also be concerning is Lindsey Halligan, Esq., as I also write about. She's named in the Executive Order.

We learn from the past to share it with future generations.